Conversation with Volker Schlöndorff, Part 2: On Billy Wilder, Steven Spielberg and Dustin Hoffman

On his hero Billy Wilder, directing Dustin Hoffman, and his misunderstood speech at the Oscars.

October 10, 2017 | by László Kriston

In 1975, Schlöndorff made The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum (1975), a film examining the impact of the tabloid press and society's hysteria over the crimes of a terrorist cell called the Red Army Faction. It tells the story of a housewife whose life is ruined after it turns out that the man she had fallen for is wanted for bank robbery. Schlöndorff received a fan letter from Billy Wilder proclaiming that it was the best German film since Fritz Lang's M (1931) — quite an extraordinary compliment.

Schlöndorff drafted several answers, but feeling they were all silly, never responded to Wilder's letter. Sometime later Paul Kohner, Wilder's agent, rang him up and admonished him for upsetting Wilder by not replying to him. Kohner demanded that he go see Wilder in a hotel in Munich to apologize. From that visit a decades-long friendship of master and disciple began.

Part 2: On Billy Wilder, Steven Spielberg and Dustin Hoffman

LK: You made Coup de Grace (Der Fangschuss, 1976) after befriending Billy Wilder. The film is set in Latvia, where a countess falls for a soldier, but when she finds out that he is gay, she joins the Bolshevik guerillas. She is caught and the object of her desire carries out the execution. People swept up by history sometimes switch allegiances almost daily according to which power is occupying their territory at any given moment. It reminds me of Five Graves to Cairo where they always change the framed pictures of the leaders in the hotel lobby.

VS: Yes, the inspiration comes from Five Graves to Cairo. Billy Wilder's father ran all the railway station restaurants in Galicia. So during the First World War sometimes they were on one side, sometimes on the other side. (chuckles) Billy told it to me.

LK: Wilder had this dictum that it's either a complicated background with a simple story, or the opposite.

VS: He said this when I told him the premise of Coup de Grace.

LK: It's nice to think in rules – Lubitsch Touch, Wilder Touch – but by those parameters all of David Lynch's movies would fail, your Tin Drum would fail, and everything that is original fails.

VS: Of course! There are no rules. Absolutely! And Billy Wilder was the first one who knew it. We were always looking for rules because it's fun doing. I enjoyed doing these debates with him. Michael Barker — I sort of discovered him when I made The Thin Drum, he's the head of Sony Pictures Classics now— he befriended Billy Wilder too. He told me, "Wilder couldn't believe that you were actually doing all these movies with this serious content, and that for you seemed to be more important than to reach out to the audience." Billy didn't need to have the deeper meaning because all his movies have a very strict moral attitude. He is uncompromising on the ethics. And there is never a weakness in his movies on that. But for him it was actually kind of astonishing why someone, when it is difficult enough to make a movie, would make it even more difficult by choosing such complicated subjects. (chuckles)

He came from journalism and worked his way up the ladder, so what people call deepness (chuckles) was not something he was after. Anyhow, I thought we just had a mutual respect based on character. On personalities. But apparently there was a thing, especially towards the end when he was doing Fedora (1977), and the remake of Buddy Buddy (1981), when I was making those movies, and there was apparently something there where he thought I was doing the right thing and he was doing something wrong.

I now am trying to understand Billy Wilder in a different way. He was very, very committed when he started. Straight-on attacking the Hollywood moguls in the open when he was still a nobody. When he was doing Double Indemnity and whatnot. And when there were political compromises, like on Stalag 17, he just walked out of Paramount. [Paramount President Barney Balaban wanted to change the heavy in the picture from a German into a Polish Nazi, so it wouldn't offend German audiences. Wilder, whose mother, grandmother, and stepfather perished in Auschwitz, demanded that Balaban apologize, or he'd leave Paramount. Balaban did not. So Wilder walked out on his contract.] Later on, maybe he mellowed somehow. Or was it under the influence of Audrey [his wife] because she wanted to be respectable? Audrey was the one who didn't want my documentary [using material from the 30 hours of taped interviews he made with Wilder] to be shown. Because she felt he wasn't dignified enough.

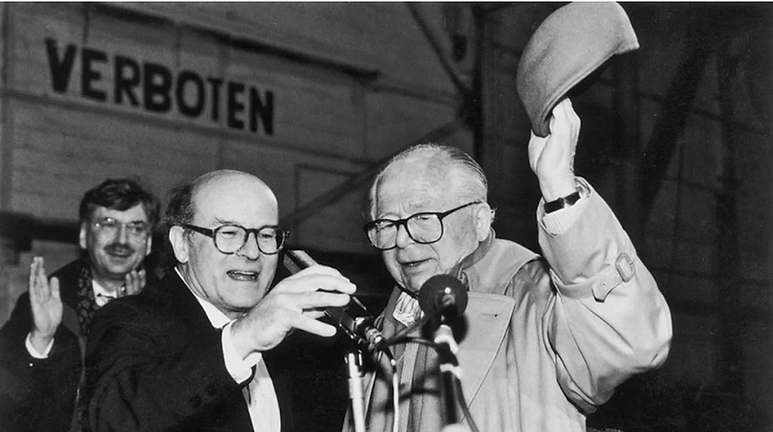

Volker Schlöndorff and Billy Wilder

LK: Because of all the back scratching with that stick?

VS: Yes. That kind of stuff. It should be properly lit. [Film historian Hellmut] Karasek made a book. But it is very bad. Even [in] the German transcript he tried to be funnier than Billy Wilder. He tried to make it a funny book. But it was not Billy Wilder. And Billy Wilder hated it so much that he did not agree to have it published in English or translated.

LK: I watched your Oscar acceptance speech on YouTube...

VS: There was this terrible misunderstanding. Which I didn't even get as I was there. I start, and I say, "The first Oscar for a German film since World War II for reasons we all know."

LK: In two instances during your speech, someone talks loud in the audience, as if he's shouting at you. I didn't understand what he said.

VS: Nor did I.

LK: You were stopped at least once.

VS: Once more. "For reasons we all know," and Billy Wilder got it perfectly. He told me, "I don't know what they have, these guys. What you meant to say was that German films were so bad after the war in the 50s, and so on."

LK: Wilder once famously remarked that "life is too short to watch German movies."

VS: (chuckles) But they thought I meant to say a conspiracy not to give an Oscar to German films, which is the last thing that would ever occur to me!

LK: I, too, assumed that you were referring to Nazism and the sins of Germany.

VS: No. The special bad quality of German films after the war, "because all the talent that made great movies in the 20s and 30s was actually here in Hollywood. I mean Fritz Lang," bla-bla-bla. I had prepared in my mind, if I get an Academy Award, I want to pay homage to these guys. But there was this misunderstanding. Whenever I make speeches, I'm always misunderstood. Don't be too complicated. Straightfoward. Don't have any innuendos. (chuckles)

We went for dinner at the Bistro at Billy Wilder's place and there was Bette Midler and everybody. And people were just congratulating and talking about the speech. But Billy was very adamant during the dinner when people brought this up, he said, "You, morons, you don't understand he could not mean that! What he meant is this and that!" But it was out in the open, and the next morning at seven on the Good Morning America show [Johnny] Carson brought it up, and said, "There is this German who wanted to give us a lecture." (laughs) Oh, god! Ridiculous. Total Hollywood. I think the same day the door was opened [to me] in Hollywood, I slammed it onto their faces. (chuckles)

But Spielberg made me an offer. Which unfortunately I never got. Because I had this wonderful, but, truly, a bit arrogant, Central-European German-Czech agent Paul Kohner who represented the old timers. John Huston. Billy Wilder. William Wyler. And then [Ingmar] Bergman became sort of his last big thing together with [Liv] Ullman and Max von Sydow. Spielberg was just producing the remakes of The Twilight Zone. I loved the old Twilight Zone. We had watched that with Bertrand Tavernier in Paris. And simply without telling me, my agent told Spielberg: "We won't consider any television offers." (chuckles)

LK: But it was a theatrical feature.

VS: No, at the time it was the television series. I would have done it. And I would have gotten along with Spielberg very well. Because he's a great craftsman and so am I. There was no reason we would not have understood each other.

LK: Your agent turned it down without consulting you?

VS: Yeah, without consulting me. Milos Forman, whom I befriended in New York, said, "Look, it's your choice, I'm sure you can make it in Hollywood. You may make in the next 10 years one or maybe two movies. If you go back to Europe you make five movies.” And in a sense I didn't feel at ease with this power struggle and all this ego fight that you have to put into it. I didn't have that within me. It is not my motivation to be the biggest, or the highest paid director in the world. I don't give a damn. (chuckles) As Günther Grass once put it, I'm krankhaft. "It is like a disease how modest you are. It is like a disease you have."

I'm a good professional I don't have any other claims as far as the world is concerned. And in Hollywood you really have to be driven. I never made career choices.

LK: Once you said in an interview in Budapest that Dustin Hoffman originally thought you directed Mephisto, and maybe someone made a mistake, and they got the wrong director to direct him in Death of a Salesman. I actually interviewed Dustin Hoffman in London not long ago, and asked him about it. He said, "It's the first time I hear this story."

VS: (laughs) It's typical Dustin. I think he is sincere when he says he doesn't remember. Most of the time I'm keeping a diary, so I can look up the day and the hour. I remember the cafe shop because it was really a life-turning event. At the end of the conversation, when we left, he said, "And by the way, you know, I loved Mephisto." (chuckles) And at that moment, I understood. "No, no, no, you are mistaken, I'm the one who did Tin Drum." He said, "Oh!" I asked, "Did you see it?" "No." (laughs) Never mind.

Anyhow at this point I was not eager yet to do the Salesman. It didn't seem obvious to me that I, as a German, should be shooting this piece of Americana. But it turned out right. Often others know better what you should do. Half of the movies I absolutely wanted to make were a mistake. But the movies that came to me through people who said, "You've got to do this, this is for you," unfortunately they were right. (chuckles) That's how little we know about ourselves.

The fact is he has his agents, his spies to find out who is in town. And when a new director arrives in New York he wants to meet him. In those days, you know. So he met me and made that confusion. European films, whether Hungarian, or German, from Hollywood they are very small and far away.

We were doing Death of a Salesman, and Mike Ovitz, who was Dustin Hoffman's agent, and the big agent back then, wanted me to come with him and made incredible overtures, hand-written letters – which is very rare thing, you know. (chuckles) That I should join him and his staff. And I didn't because I did not feel at ease with these Hollywood guys. It was Bert Fields, the lawyer, and his whole crowd. They gave me the creeps when I had to go out for dinner with them. It was horrible for me.

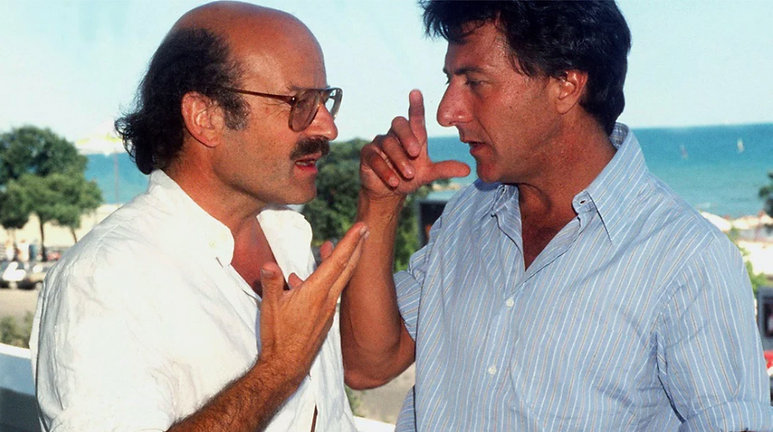

Volker Schlöndorff and Dustin Hoffman

LK: You could have been chosen to direct Rain Man. As an element in these packaging deals.

VS: I had three projects with Dustin after Salesman. One was with Leonard Dutch [Elmore Leonard], the wonderful gangster story writer. I don't know why everybody called him Dutch. [Leonard got this nickname after the pitcher Dutch Leonard when he served with the Seabees in the Navy - LK.] Dutch agreed to write the screenplay. It was a story set in Hollywood. We worked on that. I withdrew from it because Dustin always brought to the script meetings his guru kind of guy, Murray Schisgal, who wrote the play Luv. He never really signed the screenplay, but he was always next to Dustin. Schisgal was always scared. He was half a kibbitzer, and half he was rewriting dialogue overnight. I didn't get along with this guy, so I found a way out of that project after a while. Then it went to Scorsese, and he got out of it, so ultimately it was never made. You could spend years and years juggling with these projects.

In New York there was Sam Cohn [überagent at ICM]. He said, "Look, you've got to do this Handmaid's Tale." "You really believe so? I'm not so sure about this whole thing." "Yes, yes, yes."

LK: Wasn't The Handmaid's Tale (1990) an attempt to reflect on the Nazi era's race purification and eugenics, controlling who can procreate and who cannot?

VS: Of course. All that. I was too new in the United States, I was not yet fully into its culture, so I didn't take that puritanism seriously. I thought that is the past. I didn't believe anything like reborn Christian or anything like that could happen in the United States. This was before the Bush Jr. years. Ten years later I fully understood I would have made it much more aggressive.

Why didn't I make it in Hollywood? Probably because I never really wanted to, deep inside. I loved New York and I still love it today. I came from Europe and I got stuck in New York. I never went the extra mile. (chuckles) New York was then as it is now the city of independent filmmaking. The films that I made in the United States, Death of a Salesman; then A Gathering of Old Men, a film in Louisiana with Lou Gossett, Richard Widmark and Holly Hunter; then The Handmaid's Tale in North Carolina, you see, it's all on that coast. It was all independent New York producers. And I was very happy to work with them. Actually, they were eager to see how can we work in a non-Hollywood way. That you don't need a team of 200 or 300 to make a movie. I would have stayed in the United States, I felt very good working there, if on November 9th I had not been sitting on an airplane from New York to Boston with my producers to show a preview of The Handmaid's Tale in Boston. In a shopping mall. The pilot announced, "In Berlin the wall just came down." I mean instead of announcing the outside temperature – which nobody is ever interested in, but they always tell you that – for once he gave some interesting information. And immediately I thought, what are you doing here? You should be in Berlin! There will be stories there to tell. Two different societies will get together, there will be sparks. Instead I got involved in the studio business, heading Babelsberg studios. Major mistake of my life.

My wife, by the way, says I accepted the job strictly for vanity reasons.

AUTHOR

Laszló Kriston is a film critic and journalist based in Budapest.